Another day, another book to review. This time, I’ve had the pleasure to put my thoughts after reading “Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World”(2019).

Author David Epstein is a great storyteller, but what’s more important is all the values he’s packed into all 12 chapters of the book. Let’s begin!

Jack Of All Trades VS Master Of One

“” This is probably one of the most frequently asked questions of all time. This comes with a notion that if you have any inkling of a future goal, then you should train early, focus intensely and get into it asap. In short, get hyperspecialized!

Hyperspecialized is the idea that by singularly putting all efforts, including early head start, rigorous hours of practice and laser-sharp focus, then one can achieve the level of perfection or professionalism to succeed in life.

But in his book “ Range”, Epstein challenged the idea of hyperspecialization as he dove deep into data and real life examples. His alternative approach is colored with complex obstacles and messy routes to success, rather than the straight path to it.

It does not mean that specialization is unnecessary or wrong, since both range and specialization are necessary for human progress. What Epstein is trying say is that range is not to be disregarded as a failure, but rather a celebrated way of life that can still lead to fulfillment.

Two Types of Learning Environment

Speaking of paths and routes, Epstein mentioned how there are generally two types of learning environment : Kind learning environment vs Wicked learning environments. This concept is actually coined by psychologist Robin Hogarth and is often used by many researchers, thinkers, phycologists and so on. So what are they?

Kind learning environments

:

Think of a situation where the rules are relatively simple, known and you can generally expect a certain of outcome based on the efforts.

This is a kind environment where a learner improves by engaging in the activity and trying to do better. There may be a certain repetitive patterns with not a lot of surprises involved. The more you train, the better you likely will be. Examples : certain sports like chess or golf, music and games.

Wicked learning environments

:

Then there is the opposite of kind, where the rules are not only unclear but there is no immediate feedback based on your actions or performance. Even if there is, it may be delayed, inaccurate or both. There may or may not be repetitive patterns, mismatches, results that are almost improbable to predict.

In this case, wicked environments will reinforce wrong types of behaviors. Examples of this environment can be found in certain types of sports, business settings and even life.

Knowing this two types of environments is crucial to our process of learning. In the kind environment, one can learn to automate and improve significantly based on previous experience. Whereas in the wicked environment, the lack of clear rules makes it hard to plan or specialize in.

Epstein further states, “ The kinder a learning environment is, the more amenable it is to both specialization and to being automated”

The Most Powerful Chapters In “ Range”

Overall a wonderful read, I thought I’d share some of my favorite chapters to summarize the book. These are the ones that struck a chord with me, and I hope it can be a source of learning for you too.

Chapter 1: The Cult of the Head Start

The book begins with a story of Laszlo Polgar, a Hungarian who decided to home-school his three daughters and make them chess experts. See, this is straight away an example of a kind learning environment where the father thought that the world can be conquered in one exact same way.

Psychologists Gary Klein and Daniel Kahneman independently explored the link between experience and expertise. They both found that , in many real-world endeavors, repetition did not lead to improved performance or learning - with chess and golf being exceptions to the rule.

In other activities, hyperspecialized efforts rarely work especially in a wicked learning environments. Take athletes with superhuman reflexes when training or competing, they do not necessarily display the same reflexes or speed when tested outside of their sport context.

Epstein further states that hyper specialization can quickly change the status quo and render experts obsolete - even in chess game! When an AI is equipped with endless chess strategies, it is very likely to win over grand masters. The possibility is there.

In the same chapter, Epstein also writes the story of Anson Williams, one of the most successful “centaur” human players. The term “centaur” refers to someone who uses a combination of computer skills, strategic thinking and decision making ability. Since his teenage years, Williams had been outstanding at the video game Command & Conquer, known as a ‘real time strategy’ game because players move simultaneously.”

As a centaur, Williams uses empathy, creativity and human intuition to go against the brute force of technology in memory, countermoves and strategy. To be successful in online chess game, it turns out that memorization is not the key, but rather the ability to integrate broadly.

Using chess as an example, it says a lot about hyperspecialization. It is the flexibility to adapt in a wicked learning environment - not the kind setting- that is proven to be more effective in achieving success.

Chapter 5 : Thinking Outside Experience

In Chapter 5, Epstein told a story of Johannes Kepler, a German Astronomer and a key figure in the law of planetary motion. He lived during 1571-1630. In his lifetime, he had no concept of gravity, physical forces or momentum - all of which would be introduced by Newton later on ( 1642-1726).

For Kepler, analogies were all he had. Whenever he was stuck, he would use whatever limited tools in his work and got into deep analogical thinking. To think analogically is to take something new and makes it familiar, or vice versa, seeing something familiar and put it into new context. This was Kepler’s method in landing his understanding of planetary notion.

It sounds simple, and even is used in modern teaching. Students might learn about the motion of molecules by analogy to billiard-ball collisions; principles of electricity can be understood with analogies to water flow through plumbing.

But the thing with single analogy is that, we can be prone to the “ inside view”. This is a term coined by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Inside view is what happen when we draw judgments using limited resources or experiments, jeopardizing its validity.

The opposite of it, the “outside view” works more conclusively in probing deeper, forecasting further and combating biases bolder. This sounds like a better and more comprehensive way to reach conclusion right?

But it is not always in our nature to take the outside view, simply cause we would tend to see structurally similar analogies. We would look for the familiar and compare them, not circling around it from different angles over and over again. Even for experts, that’s how conclusions are generally drawn.

To employ outside views, one would have to switch from a narrow mindset, to a broader one. And that is not at all easy to do.

One company took the outside view approach in improving its movie recommendation algorithm. Instead of analogizing one user to another with similar viewing histories, it takes the bolder step and recommends other far-reaching movie predictions. The variations may stray, but the algorithm works better in capturing the rich complexity. Hence, it can come up with more accurate recommendations. The company is Netflix.

In a similar case(2001), the Boston Consulting Group created an intranet site in the effort to boost wide-ranging analogical thinking. Consultants can access the site and find all sorts of interactive ideas, from discipline (anthropology, psychology, history, and others), concept (change, logistics, productivity, and so on), and strategic theme (competition, cooperation, unions and alliances, and more).

You would think that a business consultant company would rather focus on business concerns. But that’s where they got it right, making them one of the most successful in the world.

More studies have also found that successful problem solvers are more able to determine the deep structure of a problem, before they proceed to match a strategy to it. Instead of superficially or explicitly challenging the problem, they look for non-domain context and run with it.

As education pioneer John Dewey put it in Logic, The Theory of Inquiry,

Chapter 9: Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology

Focused frogs and visionary birds. Those are the two things of focus for the world-renowned theoretical physicist and mathematician Freeman Dyson.

"Birds fly high in the air and survey broad vistas of mathematics out to the far horizon," Dyson wrote in 2009. "They delight in concepts that unify our thinking and bring together diverse problems from different parts of the landscape. Frogs live in the mud below and see only the flowers that grow nearby. They delight in the details of particular objects, and they solve problems one at a time."

As a mathematician, Dyson labeled himself a frog, but contended, “It is stupid to claim that birds are better than frogs because they see farther, or that frogs are better than birds because they see deeper.” The world, he wrote, is both broad and deep. “We need birds and frogs working together to explore it."

In this chapter, Epstein explores lateral thinking or the recombination of ideas from different domains. Meanwhile, withered technology means ubiquitous tech that is old, cheap, well-understood. When mixed together, it can be a powerful tool to success.

Example: A widely recognized scientist at 3M, Andrew J Ouderkirk worked together with his group of specialists and generalists in examining patents. Both made equal contributions.

The group also unearthed one more type of inventor. They called them “polymaths," broad with at least one area of depth. The polymaths had depth in a core area—so they had numerous patents in that area—but they were not as deep as the specialists. They also had breadth, even more than the generalists, having worked across dozens of technology classes.

When the frogs and the birds of the world are combined, no high-repetition is needed. In fact, it is proven to negatively impact performance. Years of experience also had no impact at all. Two researchers found this by studying comic creators to see what helped them make better comics.

It turned out that, long hours or overworking was not the key to better creations. But the answer was how many of twenty-two different genres a creator had worked in, from comedy and crime, to fantasy, adult, nonfiction, and sci-fi.

This study is titled Superman or the Fantastic Four? The researchers further wrote, "When seeking innovation in knowledge-based industries, it is best to find one ‘super’ individual. If no individual with the necessary combination of diverse knowledge is available, one should form a ‘fantastic’ team."

Chapter 10: Fooled by Expertise

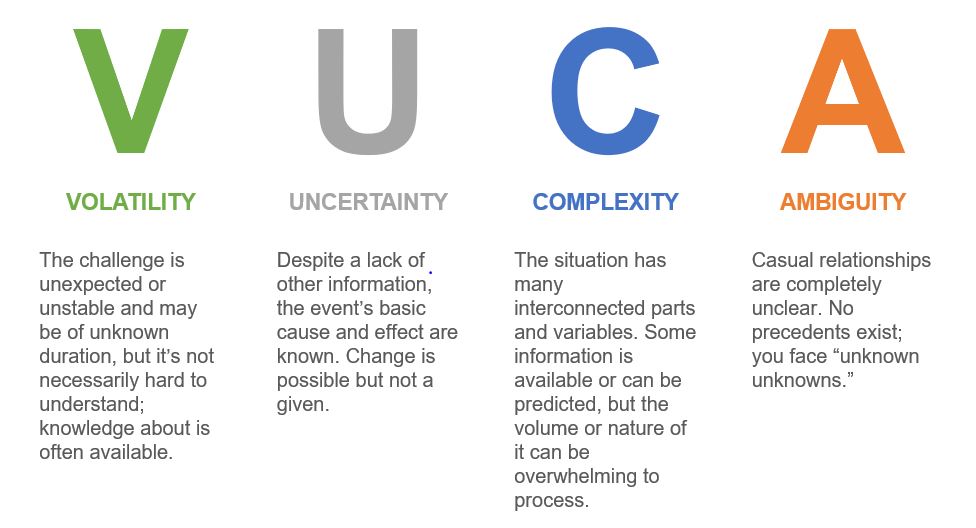

The leadership theories of Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus introduced the term VUCA : Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity. In the constantly changing world, VUCA explains why no one can really be an expert.

Based on many studies, experts are terrible forecasters of the future. Few findings are as follow :

Whether it’s a short-term or long-term forecasting, their areas of specialty, years of experience, academic degrees, and even (for some) access to classified information made no difference.

When experts declared that some future event was impossible or nearly impossible, it nonetheless occurred 15 % of the time.

When they declared a sure thing, it failed to transpire more than 1/4 of the time.

The Danish proverb that warns "It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future," was right. Compared to amateurs, experts are not in better positions.

Many experts also never admitted systematic flaws in their judgment, even in the face of their results. When they succeeded, it was completely on their own merits—their expertise clearly enabled them to figure out the world. When they missed wildly, it was always a near miss; they had certainly understood the situation, they insisted, and if just one little thing had gone differently, they would have nailed it.

Or, like Ehrlich ( one of the founders of chemotherapy), their understanding was correct; the timeline was just a bit off. Victories were total victories, and defeats were always just a touch of bad luck away from having been victories too. Experts remained undefeated while losing constantly.

As concluded by Phillip E. Tetlock, author of “Superforecasting : The Art and Science of Prediction” : Between how well forecasters thought they were doing and how well they did, there is often a curiously inverse relationship. There was also a "perverse inverse relationship" where the more famous the experts, the more likely they are to be wrong.

So what is something that could be better than experts? Enter the integrators, the kind who combine the thinking from leading experts and recombine it with integrated approach to generate better forecasts.

Through studies, Tetlock found that integrators outperformed their colleagues on pretty much everything, especially on long-term predictions. Eventually, he conferred nicknames (borrowed from philosopher Isaiah Berlin) that became famous throughout the psychology and intelligence-gathering communities:

The narrow-view hedgehogs, who "know one big thing," and

The integrator foxes, who "know many little things."

A super forecaster, Scott Eastman, describes the core trait of the best forecasters as: "genuinely curious about, well, really everything." Meanwhile, psychologist Jonathan Baron termed “ active open-mindedness” as a hallmark of interactions on the best teams.

The best forecasters view their own ideas as hypotheses in need of testing. Their aim is not to convince their teammates of their own expertise, but to encourage their teammates to help them falsify their own notions.

In the case of hedgehogs vs foxes, hedgehogs tend to see simple, deterministic rules of cause and effect framed by their area of expertise, like repeating patterns on a chessboard. Meanwhile, foxes see complexity in what others mistake for simple cause and effect. They understand that most cause-and-effect relationships are probabilistic, not deterministic.

There are unknowns, and luck, and even when history apparently repeats, it does not do so precisely. They recognize that they are operating in the very definition of a wicked learning environment, where it can be very hard to learn, from either wins or losses

Basically, forecasters can improve by generating a list of separate events with deep structural similarities, rather than focusing only on internal details of the specific event in question. Few events are 100 %—uniqueness is a matter of degree, refer back to the wicked learning environment as previously discussed.

Chapter 11: Learning to Drop Your Familiar Tools #Unlearn

When American psychologist Karl E. Weick spoke with hotshot Paul Gleason, one of the best wildland firefighters in the world, Gleason told him that he preferred to view his crew leadership not as decision making, but as sense making.

"If I make a decision, it is a possession, I take pride in it, I tend to defend it and not listen to those who question it," Gleason explained. "If I make sense, then this is more dynamic and I listen and I can change it.”

He employed what Weick called "hunches held lightly." Gleason gave decisive directions to his crew, but with transparent rationale and the addendum that the plan was ripe for revision as the team collectively made sense of a fire.

From a study of 334 higher education institutions, it seemed that the most effective leaders were paradoxical. Depending on the situation, they could be demanding and nurturing, orderly and entrepreneurial, even hierarchical and individualistic.

However, it seems that leaders best able to tolerate ambiguity had the most impact. A level of ambiguity, it seemed, was not harmful. In decision making, it can broaden an organization’s toolbox in a way that is uniquely valuable.

Wernher von Braun, who led the Marshall Space Flight Center’s development of the rocket that propelled the moon mission, balanced NASA’s rigid process with an informal, individualistic culture that encouraged constant dissent and cross-boundary communication.

He started "Monday Notes" where every week engineers submitted a single page of notes on their salient issues. Von Braun hand-wrote comments in the margins, and then circulated the entire compilation. Everyone saw what other divisions were up to, and how easily problems could be raised. Monday Notes were rigorous, but informal. More importantly, it brought everyone towards mutual success.

The success in a learning culture is one that allows opinions from anyone at anytime. Especially as a CEO or leader, the ability to see from others’ perspectives can be extremely beneficial. It offers multi lenses of a situation, giving new insights and the humility to realize that nothing or no one is omnicompetent.

Chapter 12: Deliberate Amateurs

Epstein ends the book with what I personally think as THE MOST IMPORTANT LEARNING OF ALL. It all boils down to being curious enough to learn adjacent skills.

Needless to say, this goes everything against the idea of hyperspecialization, since you would be require to constantly branching out to new skills with no specific requirements to master them. In fact, we are to avoid hyper specialization - especially in the age of digital marketing.

Think about it : what if different teams in the same company get specialized to a point that no one is talking to the other? It created siloed and disconnect the journey. Customers does not live in your siloed, they go across different touch points. So don't assemble teams separately, let them exchange ideas.

Leaders often see lunch time as waste of time. But as researcher Arturo Casadevall of Bloomberg & John Hopkins School puts it, " People grab lunch and bring it into their offices. They feel lunch is inefficient, but often that’s the best time to bounce ideas and make connections."

Or Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote a century ago, of the free exchange of ideas, "It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment."

While there is nothing inherently wrong with specialization. We all specialize to one degree or another, at some point or other. At its core, all hyperspecialization is a well-meaning drive for efficiency—the most efficient way to develop a sports skill, assemble a product, learn to play an instrument, or work on a new technology.

But inefficiency needs cultivating too. The wisdom of a Polgar-like method of laser-focused, efficient development is limited to narrowly constructed, kind learning environments. Still, it’s a wicked world we’re living in, isn’t it?

Conclusion: Expanding Your Range

Epstein’s one sentence of advice: “”

So, we’re not the Tiger Woods of the world, who received training as soon as he could walk. But everyone has the potential to be like Roger Federer, whose specialization occurs later in life after different and early unstructured activities.

Everyone progresses at a different rate, so don’t let anyone else make you feel behind. You probably don’t even know where exactly you’re going, so feeling behind doesn’t help. The key is to keep on creating, diversely and boldly.

Thomas Edison held more than 1.000 patents, most of them are trivial. Shakespeare wrote countless in-between plays. Howard Scott Warshaw designed both the award-winning Yar’s Revenge video game and the disastrous E.T. video game.

Go on your own pursuits, experiments, projects -whatever they might be. Be willing to learn and adjust as you go, and even to abandon a previous goal and change directions entirely should the need arise. Be someone with a range and while you’re at it, go wide before you go deep.